Marc Quinn is an artist who deals with the stuff of life itself. Famous for casting his head in frozen blood, he has now turned to sculpting disabled people — and his own children. Tony Barrell opens his fridge

THE SUNDAY TIMES, 2005

“He’s that bloke who poured gallons of blood into a big head and froze it” (overheard in the Duke of Wellington pub, Hounslow, 2005).

“That went up in flames with Tracey Emin’s tent” (the Half Moon, Crawley, 2004).

“A sculpture of an artist’s head made out of his own frozen blood was wrecked when builders turned off the owner’s freezer by accident. The piece called Self, owned by millionaire art collector Charles Saatchi, melted when he had work done on his kitchen” (Daily Mirror, 2002).

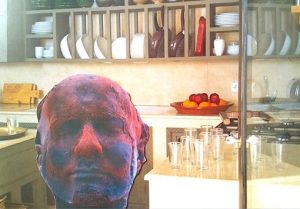

Now let’s explode some myths. Self, the cast of Quinn’s head that he made in 1991 from nine pints of his own blood, was not in the fire at the Momart warehouse last year; nor did it thaw all over Nigella Lawson’s nice, clean kitchen floor three years ago. It is still intact, carefully maintained at a temperature of around -12C, in Saatchi’s collection. Also, as with Van Gogh’s Sunflowers or Warhol’s Marilyn, there isn’t just one. Every five years, Quinn makes a new mould from his head, has another nine pints extracted over several months, and casts a new Self. So there are now three bloody Quinns gazing coldly out into the world — one is in a private collection in Dallas, Texas, and another in North Korea — and he will embark on a fourth in 2006. If you fancy it, it might set you back about half a million.

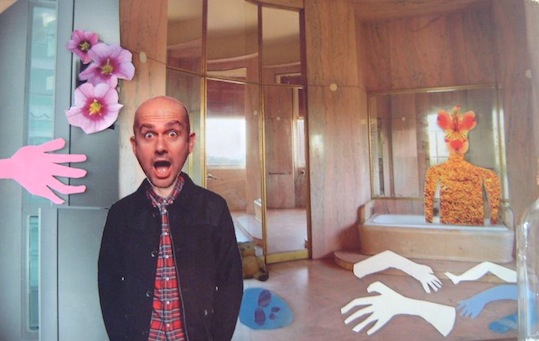

His studio is roomy and clean, but there are disembodied heads and limbs lying around

So visceral and unsettling is much of Quinn’s work that you enter his studio in Shoreditch, east London, half-expecting to face a chamber of horrors presided over by a demonic Mr Hyde. But what you get is Dr Jekyll — a neatly dressed 41-year-old man who patiently answers your questions in a soft, almost Clement Freudian monotone. The studio is roomy and clean, but there are enough disembodied heads and limbs and other more mysterious forms lying around to add a touch of surrealism, and George Harrison’s album All Things Must Pass plays in the background to remind you of Quinn’s recurrent themes of time and mortality.

That work was such a huge hit so early in Quinn’s career that I wonder whether it has become an albatross. Not a bit of it: he is still rather pleased with his Self. “I think it’s such a perfect artwork, in a way,” he says. “It’s about life and death, and it’s got an implausible quality about it, because you have to keep it frozen the whole time. I’m 100% happy with what’s happened with it. Because to make a piece of work that goes into the world like that… it opens lots of doors, and enables me to carry on making stuff which is perhaps… less obvious.”

One of the big doors that opened for him recently was the chance to make a large, very public statue in the heart of London. Later in 2005, a 3½-metre-high Quinn sculpture will be hoisted onto the vacant fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square. The work, which is threatening to eclipse Self for controversy value, is a white marble nude of the artist Alison Lapper. This is no ordinary nude: Lapper was born with no arms and short legs as a result of a condition known as phocomelia, and she is depicted as she looked when she was eight months pregnant. Green-inked letters of protest have already been flying in to the media.

“But I don’t see Alison as shocking,” says Quinn. “She’s just a person. I’m sure she doesn’t see herself as shocking when she gets up in the morning and looks in the mirror.” The square’s most famous extant sculpture is, of course, of a disabled man, and when Quinn was asked to submit a proposal for the plinth, he chose “a subject matter that was as far away as possible from what has previously been put on public monuments, which is usually male, military and triumphalist. And somehow the fact that Alison’s pregnant makes it a monument to the future. It’s all about the way that our consensus is so narrow about who we choose to celebrate; it’s about adjusting one’s sense of what’s normal”.

The sculpture (pictured) is the latest fruit of a project Quinn began in 1999, after an inspirational visit to the British Museum. While looking at classical Greek and Roman statues there, many of them missing limbs, he started musing about society’s differing attitudes to damaged sculpture and disabled people. “I wondered what, if you took all these fragmented sculptures literally, the models would have looked like.” He went on to produce a series of monuments to living people who had been disabled from birth or had lost limbs in accidents.

“When I started making them, I felt they were like public sculptures from the future — because they’re sculptures from a society that can celebrate difference.” Quinn oversaw the sculpting of these works by experts at a big workshop in Pietrasanta, northwest Italy, and admits that the Italian artisans, accustomed to chiselling out heavenly saints and angels, were “a little bit shocked” when they were presented with the commission. In his latest show at London’s White Cube gallery, he has taken this theme further with two busts of blind people. “Another dominant feature of classical sculpture is blind eyes, which you don’t see as being actually blind, so I wanted to address that issue too.” When some of his marbles were shown in New York last year, a critic suggested he was exploiting people’s misfortunes for art and profit. “That’s ridiculous,” he counters. “I’d say that disability will hopefully profit from me. When the Alison Lapper won the plinth, some guy from a disability charity said to me, ‘You’ve done more in six months than we’ve done in 10 years to raise the profile of disabled people.’”

Nevertheless, like other members of the generation of Young British Artists that Quinn belongs to, he does seem to enjoy tackling taboos and slaughtering sacred cows. Poised on plinths in the studio are a series of small, dark bronzes which look like contorted, headless bodies. What sort of deformity is Quinn confronting us with now? Are these his homage to the Elephant Man, or Michael Jackson? “This,” he says, indicating one of the exhibits, “is a rabbit.” He explains that it started life, as it were, as a dead bunny from a meat market. There are other pieces in this series that were bits of lamb, beef and venison. He used a knife, a saw and an axe to remove the parts he didn’t want.

“Then I put the meat in the position I wanted, put it in the deep freeze, and when it was frozen I made a mould of it.” Each mould was used to make a finished bronze. “And you end up with something that looks like a Rodin sculpture. Really, it’s about the way that we try and differentiate ourselves from animals, when in fact we’re all animals — we’re all flesh. You can’t make ordinary figurative sculpture any more — you know, it’s totally irrelevant to get some clay and just make a figure — so I thought, well, if you make figurative sculpture out of flesh, instead of trying to make clay look like flesh, somehow that feels more contemporary.”

So his art is not simply about shocking people, making headlines? “You know what? The truth is, I’m shocking myself — challenging my own conditioning. And because I’m like everyone else, it challenges other people too. Each time I make something, it challenges me to begin with, and it’s only when I get that frisson that I think something is interesting.” He did feel squeamish, he admits, about using all that blood in Self. “And also, chopping up all those animals wasn’t much fun. It was quite intense; it was strange.”

If you want to sum up the intense and strange art of Marc Quinn, you might call him the posh Damien Hirst

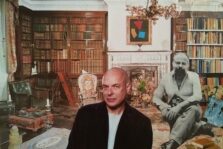

A lot of his work, says Quinn, “is about incarnation — what it is to be in the flesh body”. If you wanted a snappier soundbite to sum up the intense, strange and diverse art of Marc Eugene Quinn, you might call him the posh Damien Hirst. Official biographies say he was brought up in “London”, but it’s stretching a point: he was raised in Englefield Green, a verdant Surrey enclave south of Windsor, where church choirs sing sweetly and they still have cricket and fetes on the village green. His mother, Renee, is a French artist and potter, and his father, Terry, is a physicist.

Marc came along on January 8, 1964, and his earliest sculptural memories include modelling a duck from marzipan and eating it, and customising the model aeroplanes hanging from his ceiling — “I’d use wire wool for smoke, and put red paint on it to look like flames.” He also recalls being entranced, at the age of eight, by Tutankhamun’s death mask when the Egyptian king’s big show came to the British Museum in 1972. “It was probably a subconscious inspiration for Self,” he understands now.

After boarding at Millfield public school in Somerset, Quinn secured a place at Cambridge University to study the history of art. “I was on the very straightforward track of going to university and getting a job,” he says. But in his year off before Cambridge in the early 1980s, he found work assisting the Welsh sculptor Barry Flanagan, whose bronzes of leaping hares and trotting horses helped to crystallise the teenager’s ambition to become an artist. “And by the time I got to Cambridge, I knew I wasn’t going to want or need the degree, so I didn’t study academically that hard.” Did he graduate? “I don’t know. I did the exams. I didn’t go to the graduation — I don’t know if that means I graduated or not.”

Degree or no degree — the question quickly became irrelevant, because “a couple of years” after Cambridge he was lucky enough to meet and impress the now famed art dealer Jay Jopling. “And we did a show together.” Sadly, this debut has left little impression on Quinn himself. “There was a head made of lead, and a few other things… I can’t remember what they were.

“I was Jay’s first artist. Then, suddenly, all these other artists from Goldsmiths [College] appeared on the scene, and the whole thing just took off.” Thus he found himself at the birth of the Britart bonanza that saw YBAs making big headlines and serious money — and he was sharing a flat in Waterloo, London, with one of those Goldsmiths alumni, Damien Hirst. “We were making art about real life,” says Quinn. “It was like a breath of fresh air in Miss Havisham’s front room.” If his recollections of this period are patchy, there’s a good reason. Caught up in the hedonism of the time, he became a habitual imbiber; an alcoholic, in fact. Even the idea for that work was conceived when he had a thumping hangover. So maybe there are only eight pints of blood in it and one pint of alcohol? “No, because it wouldn’t have frozen,” he chides soberly.

Drinking stops you from being able to turn ideas into reality. I’m much more prolific since I stopped

At one point he was lucid enough to pick up a magazine, where he read about a man he knew — the doctor who had taken all that blood from him in the name of art. The magazine revealed something Quinn hadn’t known: that this doctor specialised in addiction. “So I phoned him up and he said, ‘I was wondering when you might give me a call about this.’ He must have known all along.” Now, dry for 11 years, he fiercely rejects the romantic notion that drink is fuel for creativity. “When I gave up, one of the great fears was ‘I’ll never have another good idea again.’ But luckily, it turns out that isn’t the case. The idea is insane. Drinking actually stops you from being able to turn ideas into reality. I’m much more prolific since I stopped.”

The iconoclastic artist is now a devoted family man, having apparently recast the happy, creative household he grew up in. His wife is the author of the Molly Moon series of children’s books, 39-year-old Georgia Byng — actually Lady Georgia Byng, daughter of the Earl of Strafford — and they live in Chalk Farm, north London, with their son, Lucas, 3, and Georgia’s daughter from a previous marriage, Tiger, 14. You won’t find Dad washing the car on Saturday mornings, though, as he doesn’t drive: “When I was drinking, it was too dangerous to learn, and then I never got round to it — but my wife wants me to.” Socially, he is drawn to inspirational types, his friends including the painter Gary Hume, the architect Lord Rogers, the ambient-music pioneer Brian Eno, and the actors Gillian Anderson and Clive Owen. His international patrons include the fashion queen Miuccia Prada, who bought his Garden 2000 piece — a huge frozen flower arrangement.

Has he made any work about alcoholism? “You could say a lot of it is about dependency,” he points out. Much of it is high-maintenance, requiring artificially low temperatures. Some of his works take this further and add an element of futility. In one of his purest series of sculptures — lifesize ice replicas of people including Kate Moss — not even high-tech refrigeration cabinets can stop his art from withering and evaporating: over a period of three months you can watch Moss make a backwards journey from megastar model to superwaif and, finally, to nonentity.

For his new show, Quinn has embodied the idea of dependency at room temperature, portraying real, everyday people who are kept alive by medication. He has cast these people in wax, in each case adding small amounts of the relevant life-saving drugs to the wax itself. For his subject Nicholas Grogan, who is a diabetic, he has added insulin; for Silvia Petretti he has added the cocktail of anti-retrovirals that keep her HIV at bay. The drugs aren’t visible in the wax, but, says Quinn: “There’s something about the materiality that I find exciting: by changing the pills, you can change the medium suddenly in a way that isn’t apparent.”

He has the passion for materials that you expect in a sculptor; but he also has a scientist’s fascination with their origins. “I bought a meteorite in New York recently, and I was looking at it: ‘Wow, this has been flying through space since the beginning of time.’ I was in a taxi, and I touched the wall of the taxi and said, ‘But so has this taxi!’ We’re all meteorites, we’re living on a meteorite, and we’re all made of stardust.”

Both the form and the content of the smallest of the new wax figures are deeply personal.

“This is my son,” says Quinn, indicating a wax baby, supine and blissfully asleep like all the other subjects. Soon after he was born, Lucas had an anaphylactic shock and had to be rushed to hospital. “It was terrifying, because we didn’t know what it was. It turned out he was allergic to milk.” So the wax used to cast this figure includes the “special milk powder” that saved his life. It must be said that this is an infinitely more serene work than the bust of Lucas he created after the boy’s birth, by liquidising part of the placenta.

In a separate new work, Quinn has cast his 14-year-old stepdaughter, Tiger, in wax mixed with freeze-dried animal blood from a slaughterhouse. “It’s called Beauty and the Beast,” he says, “and it’s about innocence and corruption. I suppose it’s also about the transition from childhood to adulthood.” If critics were once sniffy about his obsession with self-portraiture (he has cast himself in lead, rubber and ice, and exhibited his own DNA in a test tube), they could now argue that he was hooked on reproducing his children. A mock-up on his computer screen shows a gigantic white sculpture of Lucas suspended in a green landscape. “This is the 12-metre outdoor version,” says Quinn. “It’s called Natural Causes and it represents the beauty of nature, in a way.”

Quinn being an atheist, I wonder if all this monumentalism is a bid for earthly immortality. “Well, all the frozen works can only really exist in a developed society. If that goes, then they go. I hope that some things last. But if there’s a cataclysmic nuclear holocaust that engulfs the globe, it wouldn’t really matter anyway. No one’s going to be looking at art.” He turns and picks up one of his rabbit-carcass bronzes. “But then something like this might be dug up from the ground, and people will relate to it as an archeological object. It will become a puzzle.”

And what will Lucas think when he grows up and keeps seeing versions of himself in museums and parks across the world? “I suppose he’ll be used to it,” laughs Quinn. “He’ll just go, ‘Oh, it’s Dad’s boring old sculpture.’” ♦

© 2014 Tony Barrell

Visit Marc Quinn’s website: http://www.marcquinn.com

0 comments found

Comments for: THE ARTFUL MARC QUINN