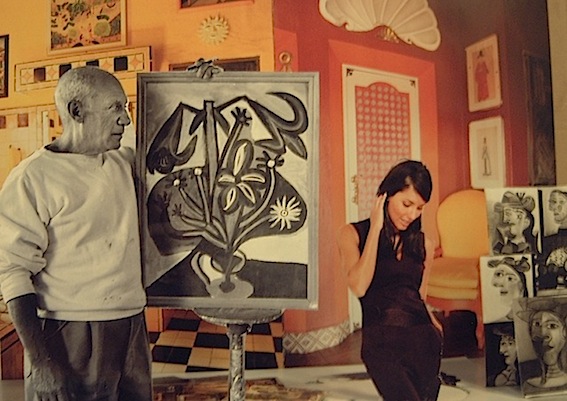

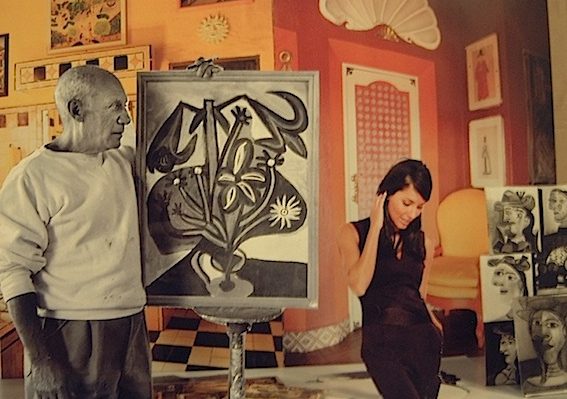

Thanks to Picasso’s paintings, Dora Maar has gone down in history as a blubbering wreck. But she was the great artist’s most fascinating muse, says Tony Barrell

THE SUNDAY TIMES, 2007

Dora Maar had the style and poise of a sexy modern-day boho art student – and this was 80 years ago. She had lustrous chestnut-coloured hair, intelligent blue-green eyes with long lashes, a husky voice, and graceful hands with painted nails. There is a story, reportedly told by Pablo Picasso, that when he caught sight of her in early 1936, at the cafe Les Deux Magots on the Left Bank, she was splaying those pretty fingers on a table and stabbing a penknife between them – playing the daring game known as “five-finger fillet”. Occasionally she would miss with the knife and self-harm, producing little beads of blood. For Picasso, an artist who loved beauty and complexity and whose work embraced cruelty and suffering as aspects of life, she must have been totally irresistible.

This was bohemian Paris, and he was Pablo bloody Picasso. He was used to having his desires indulged

There were plenty of reasons why they shouldn’t have become lovers. He was 54 and she was only 28. They were both highly emotional, moody people. And he already had two women: his wife, Olga, and his mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter, who had recently borne him a child. But these were different times, this was bohemian Paris, and he was Pablo bloody Picasso. He was used to having his desires indulged, whether they were aesthetic or carnal.

Dora Maar, née Henriette Theodora Markovitch, was unusually bright and self-reliant for a Picasso muse, a free spirit, an artist in her own right and a woman of firm political convictions. She was born in Paris on November 22, 1907, into an unhappy marriage between a woman from the Loire valley and a Croatian architect, and as a young child she was whisked off to Argentina when her father, Joseph, received some commissions there. It was here that she learnt to speak Spanish, a talent that would later give her a special bond with the Malaga-born Picasso.

By her early twenties she was studying painting and photography back in Paris. She began roaming the streets of London and Barcelona as well as Paris with her camera, photographing ordinary life, paying particular attention to blind people and down-and-outs. As fascism reared its head in the 1930s, she was drawn to left-wing groups such as Appel à la Lutte (Call to the Struggle), agitating for a general strike in France. She fell in with the surrealist art crowd, including André Breton and Man Ray, and produced strange photomontages of children lying on upside-down vaulted ceilings.

Picasso captured Dora’s likeness as a bird or a sphinx as well as a human being

In 1937, the year after Maar’s five-finger-fillet display, Picasso set himself up in a big new attic studio at 7 Rue des Grands-Augustins, and she took a flat round the corner, at 6 Rue de Savoie. Picasso captured the likeness of his exciting new muse in portrait after portrait – as a bird or a sphinx as well as a human being, and most famously in that garish 1937 painting Weeping Woman (pictured above), which has consolidated her reputation as a blubbering wreck. In fact, in the decade they spent together they had many happy times, and Picasso later said the anguished nature of his Dora portraits was due to forces beyond his control: “I couldn’t make a portrait of her laughing… For years I’ve painted her in tortured forms, not through sadism, and not with pleasure either; just obeying a vision that forced itself on me. It was the deep reality, not the superficial one.”

As he laboured on his monstrous new painting, Guernica, climbing a stepladder in his studio to reach the top of the canvas, Maar kept a photographic record

Another profound reality led to Picasso and Maar’s greatest collaboration. On April 26, 1937, German and Italian planes, following the orders of Spain’s new tyrant, General Franco, turned the historic Basque town of Guernica into a huge fireball. Picasso had just been commissioned to produce an art work for the Spanish pavilion at the World’s Fair in Paris, and he seized on the atrocity as his subject. As he laboured on his monstrous new painting, climbing a stepladder in his studio to reach the top of the canvas, which was 11ft 6in high and 25ft 8in wide, Maar kept a photographic record. Thanks to Picasso’s lover’s camera, we can see the world’s most celebrated anti-war painting slowly coming together like a big children’s colour-by-numbers picture.

One day, in front of this canvas, this depiction of warfare and its horrors, a real human battle took place. Maar was in the studio with Picasso when the other mistress, Marie-Thérèse, entered and picked a fight with her rival. Picasso told the tale of this event to his next mistress, Françoise Gilot. Basically, Walter announced: “I have a child by this man. It’s my place to be here with him.” Maar replied: “I have as much reason as you have to be here. I haven’t borne him a child, but I don’t see what difference that makes.” (This was doubtless a sore point for Maar, who was sterile.) Walter then turned to Picasso and said: “Make up your mind. Which one of us goes?” He remembered later that it was a tough decision; he was fond of both of them, for different reasons – “Marie-Thérèse because she was sweet and gentle and did whatever I wanted her to, and Dora because she was intelligent… I told them they’d have to fight it out themselves. So they began to wrestle.”

Whatever the outcome of this catfight, Maar retained her place in his affections for the rest of the 1930s and through the second world war, sharing his terror during the Nazi occupation of Paris. But they split in 1946, after Françoise Gilot came on the scene, and Maar, apparently confirming the “deep reality” Picasso had divined within her, suffered a nervous breakdown.

Requests from Picasso fans, writers and curators to visit the famous muse were spurned

By the late 1950s, after psychoanalysis, Dora Maar had entered the longest episode of her life, which could hardly have been more different from her years of partying with wild artists. She lived a solitary, nun-like life in her Paris flat and in a house in Provence that Picasso had given her, and immersed herself in Roman Catholicism as if in atonement for her hedonistic past. Requests from Picasso fans, writers and curators to visit the famous muse were spurned. She died in July 1997, aged 89, having outlived her legendary lover by 24 years.

Visiting Maar’s flat after her death, Anne Baldassari, director of Paris’s Picasso Museum, found a collection of dusty, decayed mementoes. Evoking Maar’s political passions, there was a yellowed 1944 copy of the left-wing paper L’Humanité, with the news that Picasso had joined the Communist party. And there were many love tokens from the man himself, such as a bouquet of violets in an envelope, with the message “To Dora”, dated May 1, 1937 – when he was just starting on Guernica. Another scrap of paper bears a brown blot with the simple explanation “sang de Picasso” (blood of Picasso).

Baldassari has produced a lavish volume that not only documents the extraordinary relationship between these two artists, but also allows us to appraise Maar’s own talents. We see her riveting shots of Guernica in progress, her portraits of artists such as André Breton, plus gems from her photo-surrealism period. But a 2006 art auction in New York confirmed that it is mostly as a muse, not as an artist, that this fascinating woman is remembered and valued today. Dora Maar au Chat, a 1941 Picasso painting of her with a cute little pussycat, went to an anonymous buyer for more than £50m. ♦

© 2016 Tony Barrell

0 comments found

Comments for: BELLE OF THE BAWL